Meet Us Out Back at Sunset

Mood:

down

Now Playing: The Sound of Silence

Topic: Gin&Tonics on the Tigris

down

Now Playing: The Sound of Silence

Topic: Gin&Tonics on the Tigris

Living inside the Green Zone, I didn’t get to see very much of Iraqi culture. In fact, anyone living in the Zone could easily forget that they were in the Middle East. A young man who had studied Arabic for years and volunteered for a short tour in Iraq once told me that if I had gone anywhere else in the Middle East, I would have heard the Muslim call to prayer, but he rarely heard them in Iraq. If I listened carefully, five times a day I could hear the distant sound of men calling the faithful of Baghdad to mosques for prayer, but the calls were often drowned out by the sound of my compound’s generators, helicopters flying overhead, or my music.

I had expected to see many Iraqi women wearing headscarves, officially known as hijabs. Some Iraqi women on my compound did wear a hijab, but many wore simple business casual outfits, and some wore what seemed to be designer clothes. Almost a fifth of the women often wore clothes that would have been more appropriate for an evening on the town than a day in the office. Clearly, the women I met did not fit the stereotypes that I had created in my mind for a Muslim country, and while I knew that my ideas were based on a very limited study of the region and Islam, I had the sense that my female Iraqi coworkers were not stereotypical Muslim women.

I had expected to see Iraqi men and women occasionally stopping what they were doing to pray to Allah during the work day, but if they did pray in the middle of the day, they did so in private. Religion was not something my Iraqi coworkers wore on their sleeves; for the Muslims on my compound, it seemed to be something more subtly ingrained into their souls. Interestingly, for those Iraqis who weren’t Muslim, religion seemed to be the root cause of the escalating violence in their country, and therefore it wasn’t something they liked to discuss in public.

Late in my tour, I witnessed Iraqis celebrating Ramadan, a religious holiday recognized by most people who live in the Middle East. During that time, all Muslims were fasting during the daylight hours, and the normally bustling lunchroom was empty. Each day for nearly 10 months, I had seen Iraqis loading up their plates with what might have been the best meal they received each day, especially considering that they could eat all they wanted for free. During the month of Ramadan, most of my Iraqi coworkers avoided the cafeteria, which left it without any sense of spirit. I felt like the cafeteria had almost become a private dining room for the Westerners, the TCNs, and the small handful of Christian Iraqis. Going to the empty cafeteria provided three daily reminders that Muslims in Iraq were celebrating Ramadan, but the Mission’s management also sent out an email to all the Westerners reminding us that it would be impolite to eat in front of Iraqis during Ramadan.

During that month, I also noticed small changes at the restaurants inside the Zone. Although Iraqis continued to serve food to Westerners, most restaurants decided to stop serving beer. I also heard countless rumors that some of the liquor stores were closed, and because the restaurants weren’t serving beer, most people on my compound believed the rumors, even though they weren’t true. Ultimately, the lack of alcohol at the restaurants didn’t really affect us, because we were told to limit our use of the motor pool service at sundown when Muslims broke their fast and had their first bites of food. This put a damper on any effort to visit a restaurant at dinnertime.

Most of the men on my compound also noticed Ramadan’s influence on the Fashion Channel, one of the few English-speaking stations on my compound’s satellite system. At the start of Ramadan, our cable provider temporarily pulled the plug on the Fashion Channel. In its place, they put up a short message stating, “During the Holy Month of Ramadan, the Fashion Channel will not be available.” The station normally showed beautiful women walking down catwalks throughout the world, and nearly every man in the compound guiltily admitted to watching the channel from time to time. I can even remember watching it with a bunch of other men in the same way that we might have looked at women in a strip club.

Those who watched the Fashion Channel more than they should have also knew that late at night they could watch Midnight Hot, a 20-minute burst of lingerie shows with women who had more robust breasts than the typical twiggy models. From time to time, Midnight Hot even included women in lingerie that let their perky nipples stick out, and sometimes the women were completely naked, though only for a few seconds. Every man who knew about the channel jokingly considered it a sanitized version of “Arab porn” that somehow got through government censors. The cable provider knew that while fasting, Muslims were supposed to refrain from sexual contact and lust, so the Fashion Channel and its suggestive programs had to come down for the month of Ramadan.

While much of Ramadan involved sacrifice, one of my Iraqi coworkers said it was also a time when Muslims tried to be friendlier to their neighbors. He also said that he had to avoid gossip and harmful retorts. I am not an Islamic expert, but to me, Ramadan seemed to be a time of the year that could help bring together the various members of the faith. Sadly, during Ramadan, the rates of violent attacks in Iraq went up. One of my Islamic friends dryly joked that clearly, the devoted insurgents had decided to ignore a few of the more important principles of Ramadan.

One day in the middle of Ramadan, Sabir, an Iraqi who managed my compound’s motor pool, came up to me and said, “The Iraqis working tonight are going to break the fast together around 6:30 P.M. Meet us out back behind the dining hall at the GSO trailer.”

“You want me to join you?” I asked, somewhat surprised.

“Please,” he said, and then walked away.

The GSO trailer was the kind of mid-sized trailer found in any American trailer park. When my agency first moved into its little corner of the Green Zone, it had started by converting two existing buildings into makeshift cottages, but after a rocket attack against the al-Rasheed Hotel nearly killed some of the Americans living in the hotel, my agency decided to accelerate its plans to move people from the hotel to its new compound. While the agency raced to design and build reinforced concrete hard bungalows that could safely house its staff, the agency purchased a number of trailers, installed them in its compound, and encouraged people to move into them so they wouldn’t be living in the high-profile hotel.

The trailers were modest, but they also offered a sense of privacy that couldn’t be found in the modified metal shipping containers where most State Department employees lived like canned rats. The GSO trailer was similar to the other trailers in the compound, but it also included a small kitchen. The trailer sat in the far corner of the compound with the other trailers; once all the Americans who were on long-term assignment had moved into the hard houses, the trailer area became largely abandoned, except for the night-shift Iraqis who passed their hours in the GSO trailer. While the rest of the compound slept in modestly safe concrete houses all to themselves, each night four to six Iraqis would sleep in the GSO trailer with its paper-thin metal siding.

When I arrived at the GSO trailer to break the fast with my Iraqi coworkers, I saw 10 men sitting around cheap imitation Persian rugs that they had pulled out of the trailer and laid on the ground. They had also grabbed a number of cushions from unused sofas in the nearby trailers, which had been abandoned since the Westerners and TCNs moved into the hard houses. On the rugs, the men had placed a variety of food and drink: rice, breads, dates, baklava, chicken, beer, and fruits. The door to the GSO trailer remained open so the men outside could playfully mock the Iraqi who was inside cooking more food. The cook would occasionally shout something back, and everyone laughed. I smiled because I knew it must have been funny, even though I didn’t know a word of Arabic.

“Sit, sit,” one of the Iraqi men said to me.

I sat down with my legs crossed, trying to keep my feet out of sight. During my crash course in Arabic culture provided by the State Department before I left for Iraq, I had been told that Arabs considered it rude to show your feet. I didn’t know if it was true, but I didn’t want to take any chances.

The Iraqis lay lazily around the food, eagerly passing it from one to another. Whenever one emptied his plate, one of the other men would pass on more food. I tired to take small servings, but they wouldn’t let me. The objective was clear: we had to eat every scrap of the bounty lying before us.

I felt lucky to have this moment with the Iraqi men from GSO. I had tried to show every Iraqi a great deal of respect, and whenever I could, I tried to help them. When they wanted advice on how to deal with their American supervisors, I gave it to them. When they wanted help preparing their visas and dealing with the convoluted government travel regulations, I tried to help. However, I could never give back as much as they were giving to my compound. They risked their lives every day for a few hundred dollars a month. The luckiest didn’t make more than $2,500 per month. Somehow, even though I might sometimes have stumbled when interacting with them, I had clearly made some friends.

While we ate, occasionally senior leaders from the Mission would bark out orders on the radio. “GSO, GSO, this is Shamrock. Do we have any bottled water? The dining hall is almost out.”

The men laughed and made mimicking, mocking voices, but no one responded to the call.

“GSO, GSO, this is Shamrock. I say again, do we have any bottled water?”

One of the men finally gave in and responded, “This is GSO. Could you repeat your request?”

All the men laughed. They had heard her clearly the first time, but they wanted to prod her gently to repeat herself. She did, much to the amusement of the other Iraqis, and then two men walked off to respond to the call. They walked away with their heads hung low as the rest of the men laughed and made noises, like schoolchildren mocking a classmate who had just been called to the principal’s office.

Most of the Iraqis didn’t like their American supervisors. They knew that Iraqis living and working inside the Zone were not considered as important as the Americans, yet they still wanted to be treated fairly and with respect. When they didn’t receive it, the Iraqis generally bit their tongues and accepted it. What else could they do? They didn’t want to lose their jobs. The unemployment rate had risen to nearly 50 percent, and most of those jobs paid a third of what they could receive while working for Americans, or sometimes even less. The Iraqis felt that they had no other choice, yet the pain of working for heartless foreigners cut deep.

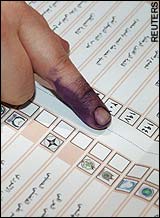

The worst example I saw of the disrespect shown by the Americans toward Iraqis happened on December 15, 2005, which was the day the Iraqi people voted to elect their permanent government. (I only wish that I could remember this details better.) Unlike the other two historic voting days during my tour in Iraq, the December 15th elections were relatively peaceful. I had heard continuous gunfire during the previous two votes, but I rarely heard the sounds of gunfire or car bombs on December 15th. Two Army soldiers who worked on my compound told me that the extremely complicated security precautions developed and refined during the previous two votes made it very difficult for the bad guys to kill anyone. I also felt that the insurgents had given up on attacking voters during the elections. The risk of getting caught or killed by Americans or Iraqi security forces, who were out in force, scared off all but the most fervent insurgent.

From 6 A.M. until roughly 7 P.M. that day, everyone living inside the Green Zone was instructed to wear body armor whenever leaving a hardened structure. As soon as that security restriction ended, I slipped back into my normal routine. I even decided to walk outside my house and carry my dirty clothes to the laundry building, even though the occasional sound of celebratory fire pierced the early evening night air. If not for the elections forcing me to pay attention to the sounds of violence and my fear that the day would take a dramatic turn for the worse, I wouldn’t even have noticed the sound of gunfire that night.

On my way back from the laundry room to my house, I saw the Iraqi supervisor of my compound’s motor pool. Sabir was a large man. At around 6 feet 4 inches in height, he towered over most of the other people working on the compound. He also had a healthy appetite. He had gained a considerable amount of weight and grown a belly the size of Homer Simpson’s due to multiple healthy servings at my compound’s cafeteria. Despite his size, he had a soft and gentle soul, and he rarely spoke more than a few sentences at a time. He often told little jokes to both the Americans and the Iraqis at just the right moment to keep everyone’s spirits high. He served as an older brother for most of the other Iraqis working in the motor pool. He did everything he could to protect them and never said a discouraging word to them in front of other people.

I found Sabir to be a model employee. He had worked for the Americans for almost two years without any problem. His English was excellent. He frequently worked extra hours without any pay. He understood the intricacies of the bureaucratic nightmare created by the Americans and could worm his way through the system whenever he needed to get something done. He also bit his tongue whenever an American treated him poorly, which happened often. He said he allowed the Americans to treat him poorly because he knew that they were living in a prison, and even a prison as nice as the Green Zone would eventually drive a person crazy.

With my laundry basket in hand, on the same night that Bush and other American leaders were celebrating, I didn’t really want to stop and have a long chat because I wasn’t in the mood to celebrate. It had been a hard week, and I simply wanted to get some sleep, but when Sabir muttered a rather sheepish “hello” to me, I slowed down enough to notice that he was moving rather slowly through the shadows. His feet were dragging with each step, and his shoulders, usually broad and bold, had rolled downward so far that he seemed like a little boy who had lost his puppy.

“Sabir, what are you doing here? I thought you had today off?” I inquired.

“I had nowhere else to go,” he replied softly.

“I don’t understand. What do you mean?”

“I couldn’t stay home.”

Earlier that day, Sabir’s best friend had given a party. His friend, Ahmad, and his friend’s family were secular Iraqis who were worried about Iraq becoming a religious state similar to neighboring Iran. They viewed the elections as a mechanism to help prevent that from happening. The constitution had given the Kurds and the Sunnis the power to band together and block the actions of the Shiite majority, who by the nature of being the largest ethnic group in Iraq could simply push the other two groups aside if the government had only given power to a simple majority.

With the new parliamentary elections, the family felt that their place in Iraq would be secured, and they also fervently believed that the secular Ayad Allawai would gain enough popular support on election day to become the permanent prime minister. They were wrong. Allawai’s Iraqi National Accord party only received 14 percent of the vote, well behind the leading Shiite and Kurdish parties. On September 15, 2005, Allawai became largely irrelevant. However, Sabir’s best friend would never learn what happened during that historic election; he had died that morning.

While Sabir’s friend and his family were celebrating the elections in the courtyard behind their house, a stray bullet flew into the courtyard and then into Ahmad’s body. Although the bullet didn’t kill him instantly, the family couldn’t take him to the hospital or call for an ambulance. Due to the intense security measures imposed by the U.S. military and the Iraqi government, no one could drive an automobile that day. Without any way to get immediate medical assistance for Ahmad, the family frantically called Sabir, perhaps hoping that his connections could help the family overcome the roadblocks, security checkpoints, and driving restrictions imposed for the elections.

Sabir had no magical powers. When he received the phone call, he did the only thing he could: he walked for over an hour to reach Ahmad’s house. By the time he arrived, Ahmad had died. Sabir, after seeing his friend’s dead body, chose to do what he could to help his friend’s family. He went to get ice to preserve the body and inquired about coffins that could be used for the burial.

In the midst of handling these unpleasant tasks, he called his American supervisor and asked to have the following day off so he could continue to help his friend’s family. His boss said no and told him to arrive for work as usual the following morning. In an effort to control his anger and block off his feelings of grief and sadness, Sabir had walked to my compound, sent a night-shift driver home, and decided to work as much as possible for the coming days. He didn’t know what else to do.

As I looked at him, I wanted to reach out and hug him. I wanted to explain how I understood what had happened to his country. I wanted to explain that my country had to accept responsibility for the instability in the country that had killed his friend. I wanted to explain to him that even though his boss was cold and heartless, she wasn’t a typical American. I wanted to say so much, but I couldn’t. What could I say to a man who had just lost his friend to a meaningless stray bullet?

All I could say was, “I am so sorry.”

“That’s okay,” Sabir muttered. Then he shuffled off into the darkness, toward the fleet of dusty armored cars that had not been used in weeks.

Posted by alohafromtim

at 6:00 PM EST

Security. Almost every time that a dictatorship falls, a period of anarchy ensures. It happened in East Timor. It happened in the Congo. It happened in Iraq. Unfortunately, the military (or perhaps just senior Administration leaders) failed to plan for this highly enviable outcome. In fact, senior political leaders pushed people out of the way who questioned the plan or made comments that attacked the logical behind the basic plan.

Security. Almost every time that a dictatorship falls, a period of anarchy ensures. It happened in East Timor. It happened in the Congo. It happened in Iraq. Unfortunately, the military (or perhaps just senior Administration leaders) failed to plan for this highly enviable outcome. In fact, senior political leaders pushed people out of the way who questioned the plan or made comments that attacked the logical behind the basic plan. Politics. The typical American view is that the

Politics. The typical American view is that the  For nearly 12 months, every time I went from my compound to the Palace, I had to pass through a Marine checkpoint. During that time, I have seen the Marines beef up the checkpoint. At first it was simply a bunch of Marines who were supported by two machinegun nests perhaps 30 yards from the checkpoint. Then, they added speed bumps. Shortly after that, they added a lot of jersey barriers. Then, they added thick metal wires that could be used block off the road in an emergency.

For nearly 12 months, every time I went from my compound to the Palace, I had to pass through a Marine checkpoint. During that time, I have seen the Marines beef up the checkpoint. At first it was simply a bunch of Marines who were supported by two machinegun nests perhaps 30 yards from the checkpoint. Then, they added speed bumps. Shortly after that, they added a lot of jersey barriers. Then, they added thick metal wires that could be used block off the road in an emergency.